Kitagawa Utamaro, The Know-it-all, from the series “A Parent’s Moralizing Spectacles, 19th c., Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum, on view April 6-May 1. 喜多川歌麿《教訓親の目鑑 理口者》19世紀 東京都江戸東京博物館

No matter how much a woman enjoys lovemaking, it has to be fit in around the more mundane activities of life, whether that be cooking, child rearing or work. It therefore seems appropriate that a new exhibition examining the lives of Japanese women as pictured in ukiyo-e paintings and prints, originally envisioned as a show of erotic art, was broadened to include topics ranging from family to education. Through May 26, the Shoto Museum of Art, a public museum in Tokyo’s Shibuya Ward, is offering a fascinating window into the lives of Japanese women during the Edo Period (1603-1868), presented through paintings, prints, books, kimono and items of daily use.

An exhibit on hairstyles. Clothing and hairstyles were limited by class and age, and people expected to cultivate their appearance appropriately. It is possible to identify a woman’s status and age by looking at the way she dressed her hair.

Initially, the director and curators at the museum had it in mind to organize a show of the erotic prints known as shunga (literally, “pictures of spring,” a long-standing euphemism for sexual images). But shunga have received considerable attention in recent years, with a major exhibition in 2013 at the British Museum in London followed by another in 2015 at the Eisei Bunko Museum in Tokyo. So when the museum tapped Aki Ishigami, an expert in the field, it asked for a broader focus.

Utagawa Toyokuni III, Owarichō, from the series “One Hundred Beautiful Women at Famous Places in Edo”(1858), Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum, on view April 6-May 1. 歌川豊国(三代)《江戸名所百人美女 尾張町》 1858年 東京都江戸東京博物館 前期展示

As a result, the present exhibition, The Life of Japanese Women in Ukiyo-e, is organized along ten themes: status and class, artistic accomplishments, women as objects of display and admiration, kimono, make-up and fashionable accessories, recreation and merrymaking, labor and work, family life, education and learning, and only finally, in a room reserved for those 18 and older, “love affairs and the enjoyment of them.”

The “adults only” room includes images of women enjoying sex as much as their male partners and plenty of bawdy satire.

The “adults only” room includes images of women enjoying sex as much as their male partners and plenty of bawdy satire.

At the time, marriages were arranged. While practices varied by class and occupation, women were generally married as young as 14 and a half and no later than the mid-twenties, and expected to bear children as soon as possible. The infant mortality rate averaged between 20 and 25 percent. Fathers in Japan took a more active role in child rearing than is common today, and in samurai and upper-class merchant families, the patriarch was responsible for the education of first-born sons.

Keisei Eisen, Board Game for the Promotion of a Young Lady’s Home Education, New Edition (1843-47) Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum. 渓斎英泉《新板娘庭訓出世双六》19世紀 東京都江戸東京博物館 前期展示

Japanese women of the Edo period engaged in a wide variety of labor beyond child rearing and household chores. In the households of samurai and the upper class, women handled household management, and the wives of high-ranking men sometimes made official appearances at ceremonies. Women in wealthy agricultural households helped in the management of tenant farmers, while the wives of merchants had busy roles managing servants.

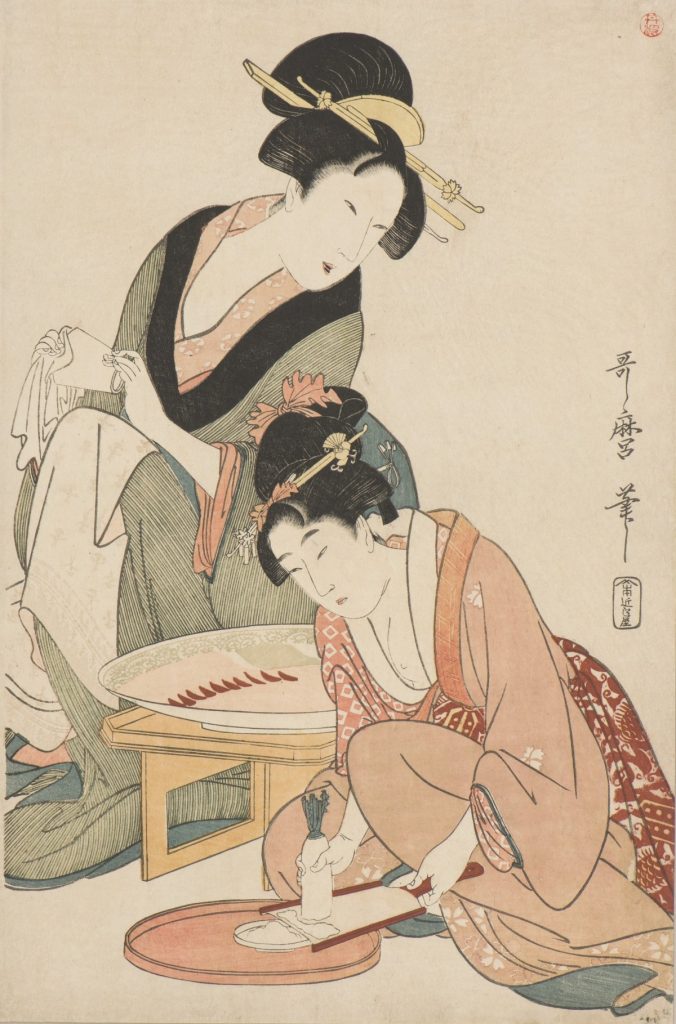

Kitagawa Utamaro, “Mother and Daughter Preparing Raw Fish,” 18th c., Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Cultural History, on view April 6-May 1. 喜多川歌麿《料理をする母娘》 18世紀 神奈川県立歴史博物館 前期展示

In family enterprises, including smaller-scale farms, shops and craft workshops, women commonly worked alongside the men while also handling housework. Women also worked outside the home, as nannies, wet nurses and kitchen maids, and many women were engaged in various forms of sex trade, ranging from the licensed and unlicensed pleasure quarters to maidservants at roadside inns who sold their bodies as well as drinks and food.

Exhibition flyer, “The Life of Japanese Women in Ukiyo-e,” April 6 to May 26, 2019 at the Shoto Museum of Art in Tokyo.

See the exhibition: The Life of Japanese Women in Ukiyo-e

The Shoto Museum of Art, 2-14-14 Shoto, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-0046

Tel: 03-3465-9421. 5-mins walk from Shinsen station on the Keio Inokashira line, 15 minutes walk from Shibuya station.

Because ukiyo-e are sensitive to light and cannot be exhibited for long periods of time, exhibits are changed several times. A full list of the works in the exhibition, with the exhibition schedule for each work, can be viewed via the museum’s website. (Only the Japanese version is available online; an English version is available from the museum’s reception desk.)

Comments