by Alice Gordenker

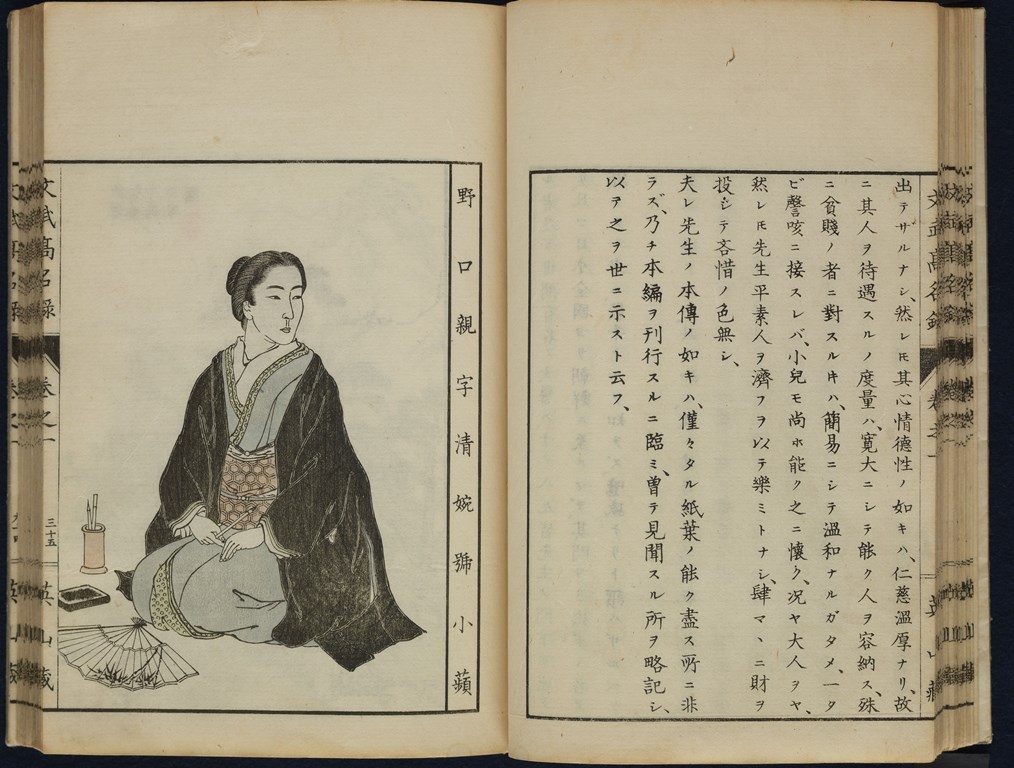

Entry on Noguchi Shōhin in Bunbu kōmeiroku 文武高名録, a compilation of famous people and important literary figures published in 1893. Private collection. Image used here with special permission.

Are you familiar with the painter Noguchi Shōhin? If not, you’re hardly alone. Even when famous in their day, female artists are more likely to be forgotten because they are studied less, exhibited less and collected less. But Shōhin – and that’s how you’ll hear her discussed in Japan because the tradition here is to refer to artists by their pseudonym rather than their family name – may be an exception. Thanks to a recent exhibition in Tokyo at the Kosetsu Memorial Museum , her work has gained attention among a new generation of historians and art lovers.

Beauty Reading a Book 美人読書図 Bijin dokusho-zu (1872), Collection of Kosetsu Memorial Museum, Jissen Women’s University

Noguchi Shōhin was born in 1847, during the Edo period, and was active as a painter throughout the Meiji era and into the Taisho years. She died in 1917 at the age of 71, having received an unusual level of recognition within her lifetime. Her work was selected by the Japanese government to be shown at the World Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893 as an example of the finest art of Japan, and in 1904, she became the first woman to receive the title of “Imperial Court Artist” (Teishitsu-gigeiin).

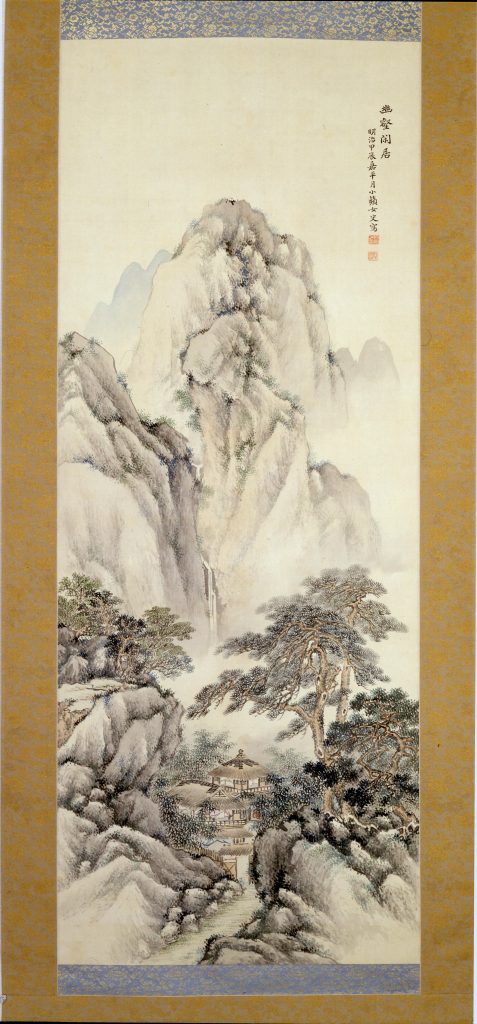

Chinese landscape with mountains and pavilion幽壑閑居図Yǖgaku kankyo-zu (1904), Collection of Kosetsu Memorial Museum, Jissen Women’s University

Shōhin worked within the Nanga (Southern Painting) traditional within Japanese painting, which is also known as Bunjinga (literati painting). Japanese literati artists generally took their themes from Chinese painting, studying and emulating the southern style of painting through imported works and books.

Crabapple Blossoms and Birds 海棠小禽図 Kaidō shōkin-zu (1910), Collection of Kosetsu Memorial Museum, Jissen Women’s University

The Shōhin exhibition at the Kosetsu Memorial Museum was small, offering approximately 15 of her paintings, but it included all the genres for which she is best known: bijin-ga (paintings of beautiful women), Chinese landscapes and bird-and-flower paintings. There were also examples the work of other Japanese female painters with connections to Shōhin or active around the same time.

The museum is always free and is located on the campus of Jissen Women’s University, just a short walk from Shibuya station. If you’re interested in the history of women in Japanese art, it will pay to keep this museum on your radar. Following the principles of its founder, Shimoda Utako 下田歌子 (1854-1936), a staunch advocate for women’s education, in 1997 the university launched an initiative to actively collect the work of Japanese female painters. (The name of the museum comes from Shimoda’s artist’s pseudonym, Kosetsu.)

All images courtesy of the Kosetsu Memorial Museum.

This post is the first installment in a planned occasional series on Japanese women artists, from both the present and the past, who ought to be well known but are not. If you would like to contribute by introducing a Japanese female artist who deserves a wider audience, please contact the manager of this blog. For more by this author on painting women of Japan, see her June 2, 2015 article in The Japan Times.

Comments