Of course they do…

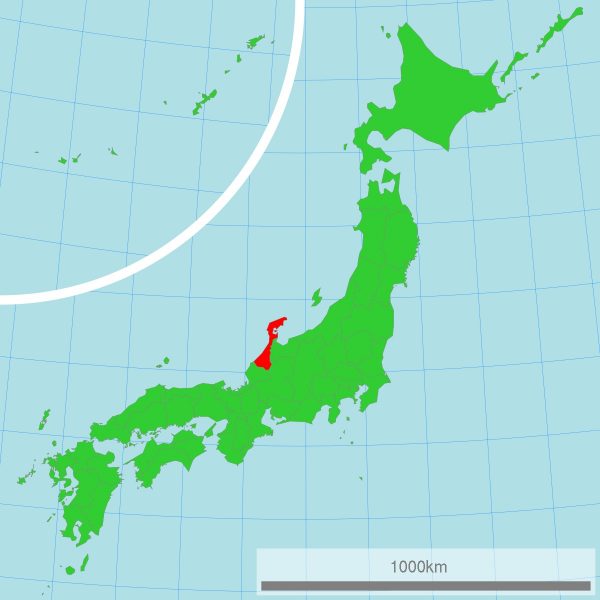

I do not get to Ishikawa Prefecture often enough. It sits nestled basking in its historical glory, on the Japan Sea side of the country, its rich history former reputation for wealth and opulence in stark contrast to mellowness and sleepiness that pervades much of the prefecture today.

During my most recent excursion there, I was able to visit a brewer called Kuze Shuzo, whose main brands of sake are called Choseimai (“The dance of long life”) and Notoji (“The road to Noto”). As is the case with a lot of Ishikawa food and drink, it’s enjoyable but hard to find near me, enough to cause one to think, “Why haven’t I heard of these guys more often, and why can’t I find this near me?”

They are unique and extremely interesting in many ways, one being that they grow their own rice that is also called Choseimai, although written deliberately with different characters. And one of the most interesting aspects of their brewing practice is the fact that they use two sources of water, one hard, and one soft.

Readers will likely recall a number of things about water used in sake brewing in Japan, including that since in the end sake is about eighty percent water, it exerts massive leverage on the nature of the final sake. And while iron and manganese need to be at very low levels to even begin to think about using a water source for making sake, beyond that brewers discuss the hardness or softness of water. This is measured by the amount of magnesium and calcium or calcium carbonate.

While one is not unequivocally better than the other, hard water encourages a fast fermentation that often leads to full sake with a quick finish, and soft water allows a slower, more lackadaisical fermentation that, when combined with lower temperatures, is conducive to ginjo production and more readily results in sake that is softer, rounder, and more absorbing.

Overall, Japan tends to have slightly soft water compared to the rest of the world. So even what is called hard water here in Japan is actually kind of soft when compared to the water in other countries.

Back to Kuze. They have a well inside the kura as do many producers, and like most places this is of course the main source of water that they use for making their sake. But just outside the brewery is another source of water, a spring that is sourced from a completely different origin, and has a significantly different mineral profile. It is, in fact, fairly hard water.

And so just for the fun of it, or perhaps just be-Kuze they can, they use that hard water for some of their sake. Interestingly, some of their products use both sources of water, i.e. both hard water and soft water in the same tanks of sake.

This of course complicates things hugely, and is in essence a nod to the history and culture of their immediate environs. And good marketing of course, if you can get people to listen to the story.

As they explained their brewing philosophy and methods to us, they eventually came to the sake that is brewed with both sources of water. And it came to light that they limit the hard water to being used in the moto, i.e. the yeast starter, and the soft water to use in the moromi, i.e. the subsequent fermenting mash.

Bear in mind that when making sake, the first milestone is the moto – the yeast starter – which takes two to four weeks to prepare, and the goal of the moto is to have a mini-batch with an extremely high populations of healthy, strong yeast. After that, more ingredients are added in three stages, roughly doubling the size of the batch with each addition, and then fermented for an additional three to five weeks, with the goal this time being more alcohol, and enjoyable flavors and aromas of course. This longer fermentation is often carried out at lower temperatures, and much more slowly, as such conditions encourage cleaner and more aromatic sake.

So when they told us that they use the hard water for the yeast starter stage, and the soft water for the subsequent longer fermentation, I immediately thought, “ of course they do.”

Indeed, of course they do it that way. While it does in fact make total sense, it is quite instructive to note why.

Remember that at the moto stage their goal is creating a strong yeast starter, and that means they want the moto to ferment strongly, so as to have the yeast reproduce quickly and healthily. And hard water will support that. Conversely, they want the subsequent moromi stage to take place more slowly, to some degree inhibiting fermentation speed, to bring out more appealing aspects of flavor and aroma in the final sake. And softer water will encourage that.

So, yeah; of course they use the hard water for the moto and the soft water for the moromi.

With about 1200 sake breweries out there today, and almost all of them making decent stuff, it is hard to do something truly unique yet still somewhat orthodox – and still be tasty enough to sell well. While it is not a choice that is open to many breweries, Kuze Shuzo has found one way to do just that. And when you hear of just how they do it, there is naught to say but “ of course they do!”

John Gauntner is one of the world’s most celebrated sake experts. He is an author, newspaper columnist and international lecturer. See John’s website at http://www.sake-world.com.

Comments