Kawai Kanjiro

By Robert Yellin

In the wake of the great tide of industrialism in the early part of this century, something of the human touch and spirit was lost in everyday articles of use. It was with a sense of urgency that Yanagi and his lifelong companions, the potters Bernard Leach, Hamada Shoji, Tomimoto Kenkichi and Kawai Kanjiro, sought to counteract the desire for cheap, mass-produced products by pointing to the works of ordinary craftsmen that spoke to the spiritual and practical needs of life. The Mingei Movement*** is responsible for keeping alive many traditions.

The output of Mingei ceramist Kanjiro Kawai (1890-1966) was so tremendous that it almost seems as if some supernatural force was guiding him. The Buddhist term tariki refers to such a reliance on grace, and it appears that he had embraced it.

“When you become so absorbed in your work that beauty flows naturally then your work truly becomes a work of art,” Kawai wrote in an essay titled “We Do Not Work Alone.” He continued, “Everything that is, is not. Everything is, yet at the same time, nothing is. I myself am the emptiest of all.”

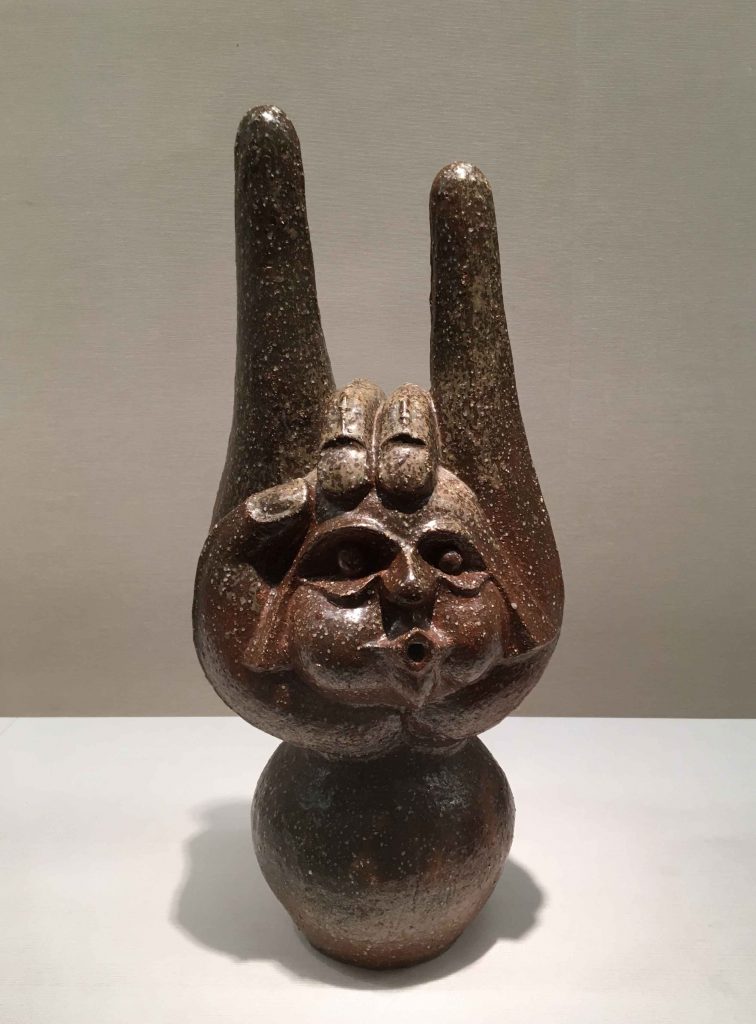

In a Western sense this would most likely be perceived as a negative and pitiful comment, but in the East it is often the emptiness and the silence that are most important. Only when something is empty can it be filled. Kawai filled his spirit and works with tariki. The somewhat eccentric Kawai was an extraordinary being, like an elf working alone late into the night; many of his pieces are full of a beauty and mystery that one can only describe as “otherworldliness.”

Kawai also never let his joy and wonder at simple things pass, even late into his years — a flower petal or the movement of his hands were causes for celebration. Like his lifelong friend Hamada, he never signed his work but said, “My work itself is my best signature.” There is no mistaking his distinctive style.

Kawai was a master of glazes, and performed 10,000 experiments on glazes while a student at the ceramic divisions of Tokyo Technical College and Kyoto Municipal Institute of Ceramics. (It was at the latter that he first met Hamada around 1912.)

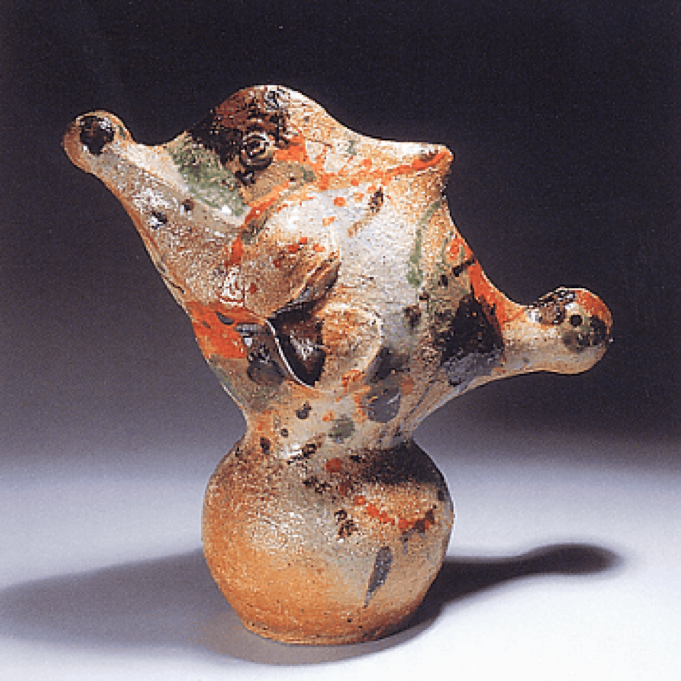

Red copper glazes (shinsha or yuriko) were one of Kawai’s trademark colors. He also used a deep brown iron glaze (tetsu-yu) and a brilliant cobalt blue glaze (gosu).

His pots come in many asymmetrical shapes and show expressionistic techniques such as tsutsugaki (slip-trailed decoration), ronuki (wax-resist) or hakeme (white slip). Two roundels (marumon) are on the front of this vase, with a single marumon on the side drawn in gosu. It has a sturdy feel, wholesome and honest, but it is so obviously Kawai’s that it sort of contradicts the “unknown craftsman” spirit of the mingei ideal. That’s one of the reasons his friend Tomimoto left the mingei group: He couldn’t justify making mingei pieces with so much personality. Kawai was full of personality and warmth. It comes through in all of his work; which includes calligraphy, wood carvings and ceramic sculpture.

Kawai didn’t allow himself the limelight, but refused all official positions and honors including that of Living National Treasure. He never lost touch with common folk and greatly respected the farmers in the countryside. “They are the kind of people we can never do without,” he wrote.

I wonder what he would make of today’s Japan. Yet even in these changing times, his work is here to remind us of the beauty that Japan once had and may be on the verge of losing.

The term mingei (folk art) was coined by Yanagi Soetsu in 1926 to refer to common crafts that had been brushed aside and overlooked by the industrial revolution. For more on Mingei, click here.

Kawai’s house in Gojozaka, Kyoto, is now the Kawai Kanjiro Kinenkan Museum.

Comments