Text: S. Beimel & H. Hasenfeld © Photos: H. Hasenfeld

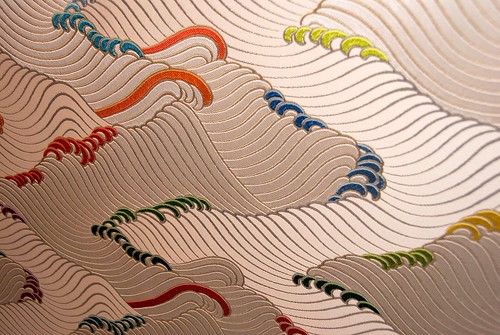

Japanese weaving is so intricate, and thus so stunningly beautiful that experts worldwide have come to both describe it and distinguish it from ordinary brocade simply by using its Japanese name, Nishiki (pronounced knee-she-key). Compared with the simple, plain weaving of European tapestries, Nishiki is three-dimensional, layered weaving.

One of Japan’s most important contemporary interpreters of Nishiki is textile designer, Koho Tatsumura. As a designer of high order, his dazzling designs have been winning him considerable international recognition. In addition to applying this high level of traditional technology to his original design work, he is actively involved in carrying forward the work of his late grandfather, Koha Tatsumura, founder of the Tatsumura Company, renowned kimono weavers since the late 1800s.

To this end, Koho established the “Japan Traditional Weaving Preservation Research Society” for the purpose of researching exceptional pieces of ancient woven cloth and reconstructing the weaving techniques required to produce them. This has enabled Tatsumura to revive weaving patterns that originally came to Japan over the Silk Road over 1300 years ago and to introduce them back into today’s culture by producing textiles for kimono and obi, items for the rarified tea world, as well as accessories for the home and office.

Both the traditional and contemporary works of Koho’s studio include commissions from the Imperial family of Japan, prestigious religious organizations, as well as the Japanese government. Such commissions bestow official support for these culturally important, highly specialized yet endangered arts. The governmental works include the official banner for the G-7 conference, and fabrics for the interior of the Geihinkan National Guest House in Kyoto.

In its desire to revive ancient methods, Tatsumura explained how The Society began by looking at textile fragments and collaborating with the Kyoto Dyeworks Research Center. Then in order to replicate ancient methods of weaving, they created looms based on the 1200-year old technology that originated in the Tang Dynasty (7th-9th century China.) “Though Tang-era looms extant in China today provided us with a reference point, we still needed to recreate the looms that subsequently evolved in Japan. For this we turned to special loom carpenters. Today, there is only one wooden loom carpentry workshop remaining in Japan and only one man left who knows how to make renowned Miyazaki shuttles from red oak.

Design layout created prior to weaving.

“As part of the time-honored culture of wood working, each loom requires a number of different types of wood, depending on the required function. In addition to authentic looms, all things connected to the weaving process have to be recreated in their original forms, even tools and thread. The first piece we completed cost us $120,000. It is now in the Soshoin, the national museum of antiquities, connected to Todai-ji Temple in Nara. Funding in the form of grants was received from companies such as Toyota (the Toyota company actually began its original operation as a loom manufacturer.) Only about 5% of our weaving process is mechanized, using a Jacquard system and run by an old IBM tabulating machine. Our system is a combination of digital and analog.”

This work involves training the next generation of artisans to do everything from processing thread by hand from silk cocoons to weaving to devising weaving equipment, not only creating jobs and keeping ancient technology alive, but also producing technical documentation that can be passed on to generations to come.

Though it typically takes ten years to learn Nishiki weaving, Tatsumura’s teaching methods allow students to gain proficiency in a fraction of that time. The traditional method of teaching most Japanese artisan skills provides little direction to students, who are expected to “learn with their bodies” by trial and error. Though this teaching method is extremely effective in training weavers to the level of true mastery, the long process makes it difficult to attract young people to the field. Tatsumura has broken with tradition, providing consistent and logically progressing lessons to students, enabling them to learn in two years or less (a time frame more appealing to those with a 21st century mentality). Koho’s son Amane, learned Nishiki weaving in one year, as did two other people who were trained using Koho’s methods. Amane, actually, is very coordinated because he was a drummer with highly developed coordination in his hands and legs. Good weaving requires good rhythm, because good rhythm translates into good texture.

Though dyeing of thread is a fairly easy process, replicating the same color over and over is not. Tatsumura depends on the highly honed skills of Japanese dyers for his works, mostly in silk. The structure of silk lends to the quality of the work. Silk is actually a prism with two pyramidal columns within each strand, creating a sparkle when light is refracted as it passes through. Additionally, since Nishiki weaving is three-dimensional, the light is further refracted. This phenomenon is referred to as ‘hikari no ito’ or threads of light.

Both the Tatsumuras’ revival work and much of their original weaving designs are funded by grants, and are marketed under the Koho label.

This article is from Behind Paper Doors–a series about remarkable people in Kyoto.

Helen Hasenfeld The Discerningeye.com

© Photos by Helen Hasenfeld